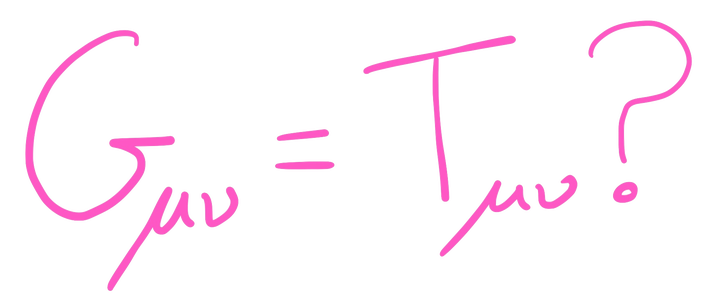

Is General Relativity the theory of gravity describing the physics of our universe? It certainly seems that way, at least it was been tested on distances from about mm (the size of an Amoeba) to m (the edge of the solar system). Technical details can be found in this article. Recently, we also have strong evidence that it also describes correctly the strong gravity regime (but low curvature) with the detection of gravitational waves from binary black holes (see also my project on gravitational waves in cosmology).

What about the mysterious dark matter and dark energy? What about the early universe when gravity was the dominant force, spacetime curvature was large and the energy scale was very high? At the moment we do not have a definite answer but we have strong expectations that there is going to be more than General Relativity. For instance, quantum gravity and string theory generally predict the presence of non-trivial interactions of scalar fields with gravity. Furthermore, observations of the Cosmic Microwave Background by the Planck team give more statistical significance to some alternative theories of gravity in the inflationary paradigm (see my works on inflation and CMB here). For an exhaustive list of alternative theories of gravity check this paper.

I study the (rich) theoretical structure of a class of alternative theories of gravity called scalar-tensor theories1–the one I mentioned being motivated by quantum gravity and string theory–and their applications to inflation, dark energy and dark matter. In my research, I mainly focus on the implications of how matter would experience gravity if there were non-trivial interactions between the scalar field and matter. This actually yields interesting results!

For example, we have argued in this paper that the infamous black hole central singularity might be an artefact due to a bad choice of metric and fields. Although we can only prove it for some examples, it is indeed an interesting possibility.